- Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers, some of which have technical and cost advantages, pose a challenge to Western automotive manufactures.

- There is potential for significant growth in market share in Europe, potentially to the levels of Japanese and South Korean brands.

- Despite the increased competition, widespread protectionist trade measures are unlikely, but western automakers face a downside risk to volumes.

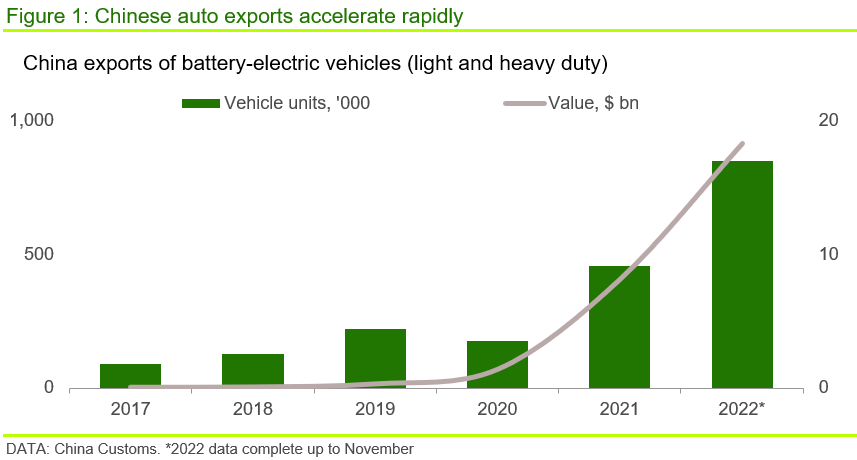

After a decade-long coordinated strategy to establish China as the global leader in battery electric vehicles (BEVs), Chinese brands are now expanding beyond the home market. Exports of BEVs from China reached a record high in 2022. The main market has been Europe, with ~ 225,000 BEVs (passenger cars and light commercial vehicles) exported. This only represents 4% of Chinese BEV production, but if these growth rates are maintained, exports will become increasingly important for Chinese OEMs and European consumers.

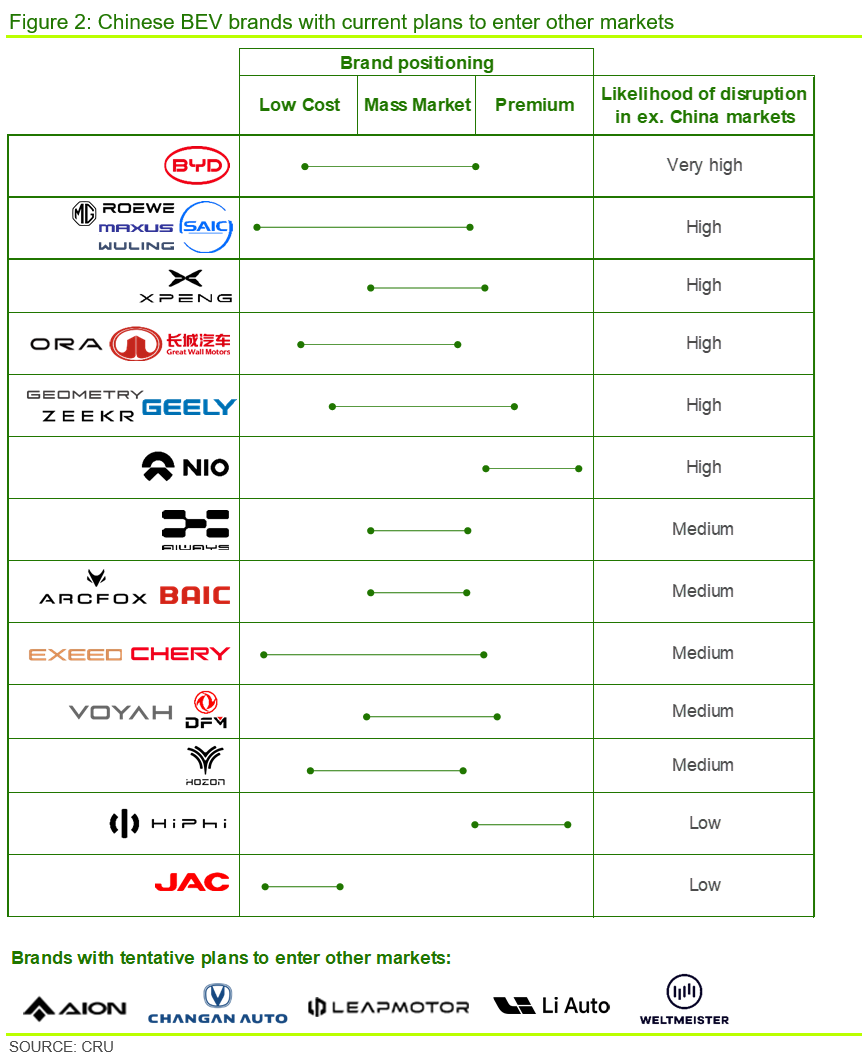

After testing a few carefully selected markets, 2023 is likely to be the year when the Chinese brands push harder, after consumers have responded well to their offering. The most prolific OEMs have been BYD Auto, SAIC Group, Great Wall Motor, Geely Group, NIO and XPeng.

Alongside plans to grow exports, many Chinese OEMs have been expanding production sites outside of China, across ASEAN and India. There are even plans for doing so in Europe.

Western brands outsourcing limited production to China

Almost 80% of Chinese BEV exports to Europe in 2022 were from western brands transplanting production to China. This will grow as OEMs make decisions on a model-by-model basis, weighing the potential cost and supply chain advantages of building in China. This could hit European assembly rates – for example the next generation MINI electric hatchback will be produced in China, implying a precarious future for the UK plant.

Other automakers that are shifting some BEV production to China include to various extents: Tesla, Volkswagen Group, BMW, Honda, Polestar, Lotus, Volvo, Smart, and Renault.

Yet, the impetus to ‘build where you sell’ for cost, environmental, and geopolitical reasons will limit this.

Chinese automakers have advantages over the competition

The lower cost of labour, economies of scale, decades-long experience in battery and EV manufacturing, dominance of raw material supply chains and favourable legislation together create a significant cost advantage for Chinese OEMs.

Yet, technical innovations have also contributed to falling costs. The best example is BYD, which has developed elegantly simple solutions to industry-wide cost and supply concerns. It has discarded battery modules, instead using space-efficient ‘Cell-to-Pack’ or ‘Cell-to-Body’ configurations in combination with long-format ‘Blade’ battery cells. This has unlocked lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries for more vehicle segments, which are nickel- and cobalt-free, and ranges are now comparable to some nickel-based vehicles.

Chinese OEMs are proven to have rapid turnaround and are better able to make design changes in the middle of vehicle model cycles. Model cycles in the automotive industry are typically around seven years.

Chinese OEMs have also been employing different business models to their western counterparts. BYD, among others, has been pursuing a strategy of vertical integration, from the raw material stage down to the battery pack.

Another boost for Chinese OEMs have been the dual credit policy for New Energy Vehicles (NEV). Automakers receive credits based on vehicle production, not just sales, and so are incentivised to export more vehicles.

How much share can Chinese brands gain?

A historical parallel can be drawn – when Hyundai-Kia tried to enter the European market, or when Toyota and Honda tried to enter the United States, policymakers made it difficult for them to operate, but consumers still wanted their products. Eventually those brands became well-established, and production was partly localised.

Some consumers, particularly those whose choice is driven by costs and performance advantages, will increasingly consider shifting to Chinese BEVs.

The higher costs and tighter margins in BEV manufacturing has resulted in a general trend upmarket to larger/premium vehicles segments at many western OEMs. This has left a vacuum that Chinese OEMs can fill. Nevertheless, the likes of NIO – which have stated a desire to be servicing users in 25 countries and regions by 2025 – are also fighting for the premium segment.

Brand awareness and loyalty also remain barriers, and there is still a general perception of Chinese vehicles being of poor quality despite the reality.

We expect that China will look to the European market first to grow exports. We also anticipate that Chinese brand BEV sales in Europe could grow to 1 M units at the low end, and to 2.3 M units at the high end. The latter is the equivalent to the Japanese and South Korean brand volumes in Europe currently.

China will look to grow exports to other regions also. Most Asian markets (ex. China) remain relatively small for BEVs, but altogether could add significant volumes. While we expect Chinese OEMs will look to sell in the US too, this could prove more difficult, principally due to trade policy and fraught geopolitics.

Trade policy and localisation of production

The cost competitiveness of Chinese automotive benefits from favourable trade policies. Vehicle imports from China to the European Union attract a 10% tariff, while imports into China attract a 15–25% tariff.

Depending on the success of Chinese brands in Europe, policy makers could come under pressure to raise tariffs to protect local industry. We expect strong lobbying efforts from major European automakers, unions, and potential changes in public opinion.

Yet, it is not a simple case of simply increasing import tariffs. Such measures could spark a reactionary restriction on European automakers’ activities in China. The two markets are highly intertwined and China is a major part of a global supply chain, so further protectionist trade action is unlikely.

What is more likely is that governments subsidise domestic OEMs, for example with cheaper energy for battery production.

To avoid trade restrictions, automakers are increasingly localising vehicle production. BYD has a very embryonic plan for establishing an assembly plant in Europe, but it has already received offers of help to secure suppliers, energy, land, and labour.

This has worried European automakers, along with local manufacturers in India and ASEAN, but parallels can be drawn from Tesla’s move into China. It caused what some call a ‘catfish effect’, whereby a new entrant establishes benchmark and spurs the rest of the industry to improve their technologies and product competitiveness to catch up.

Reasons for optimism

Western OEMs are responding with improved product offerings and may increasingly adopt any of the successful operating practices and engineering philosophies of Chinese innovators. Western OEMs are also not uniform and companies such as Tesla remain a leading challenge to Chinese brands.

Western automakers will face increased competition, which will hit production rates at some OEMs, but it would be an overstatement to say that western OEMs are doomed.

Find out more about our Sustainability Services.

Our reputation as an independent and impartial authority means you can rely on our data and insights to answer your big sustainability questions.

Tell me more